A Love Like New: The End of Palm Reader

It's lunchtime when we arrive at Upcote Farm. Situated in the idyllic Gloucestershire countryside near Cheltenham, the farm is dotted white with sheep and the smells and sounds of agriculture fill the July air. A tractor trundles off behind a hedge in the distance. Some cows gather on the other side of a dry stone wall, gazing quizzically at the unfamiliar car.

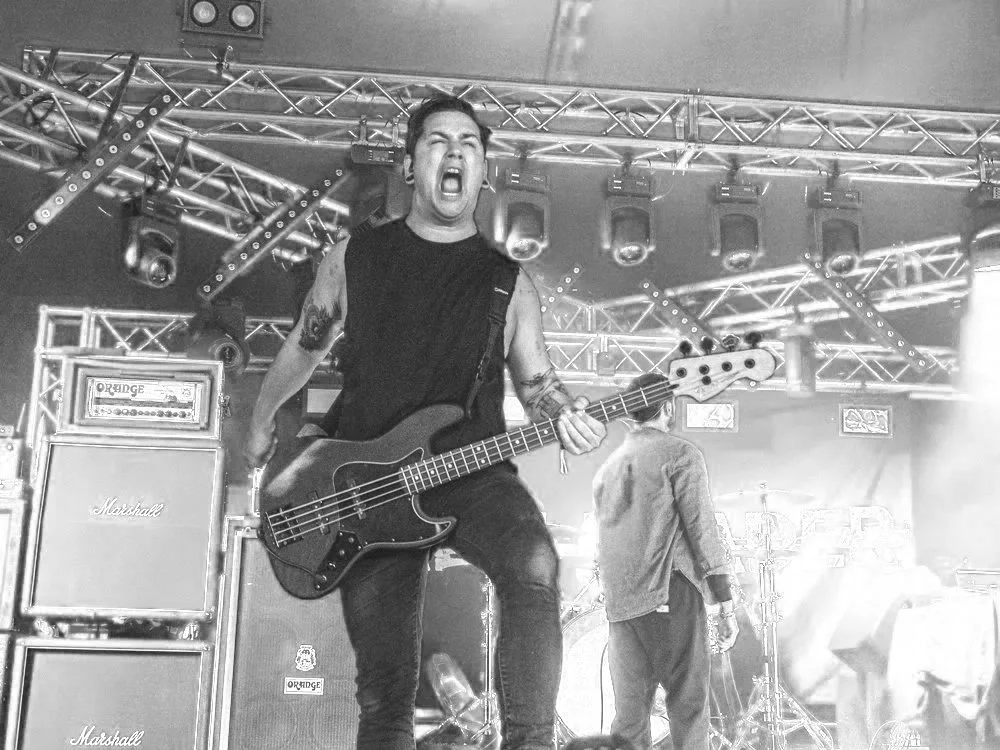

Dave Musson

It's lunchtime when we arrive at Upcote Farm.

Situated in the idyllic Gloucestershire countryside near Cheltenham, the farm is dotted white with sheep and the smells and sounds of agriculture fill the July air. A tractor trundles off behind a hedge in the distance. Some cows gather on the other side of a dry stone wall, gazing quizzically at the unfamiliar car.

At least, that's what I lazily imagine it's like for the rest of the year. This week, Upcote Farm is 2000 Trees, a music festival founded in 2007 by rookie promoter James Scarlett and a group of music-loving, festival-going friends.

For the past two weeks, Scarlett and his team have been transforming the farmland into a tiny town of stages, marquees, campsites, food trucks and portable toilet units. It’s a gargantuan operation undertaken twice a year, first for 2000 Trees in the middle of summer and later, elsewhere, for ArcTanGent.

The magic of a festival is in all the things that happen around the music. It’s in the atmosphere, in the food, in the camping, that a festival can differentiate itself. By and large, they do nothing for me. If I had a pound for every conversation I’ve had with someone surprised I’d never been to Download, I could afford to go to it.

Festivals aren’t really designed for me. I take my live music in small, intense doses, in clubs and academy venues and the occasional arena show if – and only if – it’s the only way to see a band I love.

2000 Trees is the UK’s leading big little-ish rock festival and Scarlett books some of my favourite bands year after year after year. I have the same thought every summer: I don’t go to festivals but if I did, it would be 2000 Trees.

I did go in 2019. I saw a series of bands that justified the price of a ticket twice over, ate some tasty street food and generally had a lovely time in the sunshine. I watched Turnstile, Conjurer, Haggard Cat, Milk Teeth and Jamie Lenman (twice).

And I watched Palm Reader. I always watched Palm Reader.

Having first discovered them six years earlier, by the summer of 2019 I’d seen them on countless occasions, bought nearly a full wardrobe of t-shirts and built a modest vinyl collection consisting entirely of Palm Reader releases.

The most recent at that point was Braille, which had put a band beloved by the UK underground on the map. It strengthened Palm Reader’s unwanted status as a criminally under-appreciated gem but catapulted their creative reputation into the stratosphere. It had been a tough road but the band had made it to album number three, each an improvement on the last, and were among the most respected musicians in the scene.

The classic Palm Reader line-up – singer Josh McKeown, guitarists Andy Gillan and Sam Rondeau-Smith, bassist Josh Redrup and drummer Dan Olds – needed no introduction to the 2000 Trees audience. After Woking and Nottingham, the festival had become the band’s third home.

I can reel off those five names with the same enthusiastic ease as a football supporter reciting the England team that won the 1966 World Cup final. That’s who the recorded version of Palm Reader were to me: five hard-working musicians blessed with sharpened creativity and capable of an outsized impact on the lives of their fans.

In 2024, after thirteen years, Palm Reader’s appearance here will be their last. They announced in March that the band would be coming to an end with a small final headline tour in July and a last, brief pause for breath before a swansong here, at Upcote Farm, at the festival where they feel most at home.

This is Palm Reader’s last ever show. If I’d had to, I’d have walked here.

“It’s an affront to cosmic justice that the five men who created Beside The Ones We Love were back at work the next day.”

Bad Weather is a fully formed debut album and yet a barely adequate indicator of what would follow in the next seven years. It established Palm Reader’s progressive, aggressive, intelligent and intoxicating blend. It’s raw but mature, abrasive and jagged yet melodious.

Palm Reader’s debut album oozes intensity but ‘Bitter Hostess (Grace Pt. 2)’ is their first diversion of many into beautiful, quiet interludes that boost the range of their records and show off the depth of their musical chops. From firecrackers like ‘Spineless’ to infectious anthems like ‘Seeing & Believing Are Two Different Things’, Bad Weather has the lot. It’s Palm Reader’s least best album.

The second record blew the first out of the water. Beside The Ones We Love was recorded with lightning speed in Birmingham and came out in 2015. It’s explosive but expansive and ambitious, full of crushing riffs and far more groove and thrust than an album with such harsh edges has any right to have.

It, too, was bettered in just three years. But Beside The Ones We Love is an outstanding record released in the dark days before heavy music finally emerged from an era of creative atrophy.

McKeown – not only the vocalist but also the essence of Palm Reader’s song-writing and musical identity – put in a virtuoso performance and carried it into the years of gigs and touring that followed. Palm Reader shows between 2015 and 2018 were phenomenal and McKeown was at the forefront of that, roaring through a suite of highly charged songs that sounded like nobody before or since.

‘I Watched The Fire Chase My Tongue’ was a soaring mainstay of Palm Reader sets for a decade. It’s full of twists and turns but never incoherent. ‘Stacks’ is more outwardly vituperative and was another live favourite when the band toured their second album.

Dave Musson

The real heart of Beside The Ones We Love beats behind two very special songs. ‘Travelled Paths’ is stripped back to the bone. Bands of such ferocity are seldom capable of naked vulnerability but Palm Reader, armed with the perfect singer to make it work, did it without missing a beat.

‘Sing Out, Survivor’ is extraordinary. It’s epic beyond belief and topped off with a vocal performance that holds its own not only with McKeown’s finest but those of more celebrated stars at the top of their game.

Even as their second album attracted critical renown, the members of Palm Reader grew frustrated with their lot.

As well as talented musicians, they are astute observers of the inner cells and walls of the music industry. They know what’s good and what’s not. They understand with painful clarity when the latter makes a dent the former can’t. Palm Reader were a band for people in bands, an accidental secret for fans in the know. They were underappreciated and they knew it and they felt it.

In my adolescence, rock music was so mainstream as to be barely alternative. Nu-metal was big business. Bands needed a lot of luck to get signed to a major label but those who did could make a fortune even from mediocrity. It’s an affront to cosmic justice that the five men who created Beside The Ones We Love were back at work the next day.

Between 2015 and the release of Braille in 2018, there was a real possibility that they wouldn’t make it that far. Half a decade of digging deep, grafting for the craft and producing invisible excellence was taking its toll on morale. Being darlings of a scene doesn’t keep the lights on but the premature abandonment of Braille would have been a tragedy.

Thankfully, Palm Reader stuck to their guns. The third album gave the band a new lease of life. It was an artistic triumph that broadened the scope of Palm Reader’s sound. Now perched atop the raw and ferocious, a new approach to heaviness: measured and melodic, possessed of still more emotional weight.

Braille was acclaimed as the work of a band who were all grown up, comfortable in their musical skins and willing to take a gamble in order to expand upon their sonic guts. McKeown unveiled a distinctive, characterful clean singing voice but there’s no little edge to ‘Internal Winter’.

But Braille has an added dimension. ‘Inertia’ and ‘Swarm’ are fabulous examples of the band’s penchant for towering compositions. The last track on the album, ‘A Lover, A Shadow’, is a stunning piece of music, masterfully written and performed by a band able to touch perfection.

I went to see Palm Reader often during the Braille cycle. They played in a support slot under Rolo Tomassi in Birmingham right after the album came out. Three weeks later, they performed a remarkable set at an album release show at the Bodega club in Nottingham, where they'd been based since 2015.

Dave Musson

A few months after Braille came out they supported Glassjaw at the legendary Brixton Academy. In December 2019 they played in front of a small but febrile crowd at Nottingham’s Rough Trade.

Palm Reader were reliably, routinely superb. With a diverse trio of records and three solid years of ferocious performances behind them, the band were critically revered and on a roll.

Then 2020 happened.

Before hitting the stage at Rough Trade, bassist Redrup informed me that the band would be recording their fourth album in the coming January. That night they debuted ‘Stay Down’, which turned out to be a mere slice of an exceptional record. In March, I saw Palm Reader twice in three days on their tour with Woking comrades Employed To Serve, first in Milton Keynes and then in Birmingham.

They were my last gigs until 2022. The coronavirus pandemic had a devastating effect on live music in the UK. Brexit didn't do it any favours either. With Sleepless ready and heading for the pressing plant, Palm Reader were grounded along with everyone else.

To make matters worse, the horrific scandal that took down Holy Roar Records cast the release plan into disarray. There were people hurt who matter much more than delayed albums, a point members of Palm Reader and bands similarly affected made at the time.

Church Road Records (the label run by Employed To Serve’s Sammy Urwin and, in the aftermath of Holy Roar, his bandmate and partner Justine Jones) picked up Sleepless and unleashed it on a covid-riddled world the day after the screening of a performance in an empty St Edmund’s Church in Rochdale. Palm Reader played five of their new songs in that set, ushering in the dawn of the best record they ever made.

Sleepless is Palm Reader’s insurmountable masterpiece. Polished but crushingly heavy, laden with melancholy but spiked with flashes of euphoria, album number four is a flawless construction played with fire and flair. Every song features new ideas, tones and touches with which Palm Reader hadn’t previously experimented.

‘Willow’ boasts perhaps McKeown’s finest vocal of all. ‘False Thirst’ feels half its actual length and serves up everything good about Palm Reader in one place. It’s catchy and melodic with incredible vocals and deft musicianship, but it’s monolithically heavy too.

‘Both Ends Of The Rope’ is a portentous ode to the span of Palm Reader’s career and packs one of the crunchiest riffs they ever wrote. The jewel in the crown is ‘A Bird And Its Feathers’. It’s unique even amid the Palm Reader pantheon – slower, more intense, more adventurous than anything else..

Dave Musson

I took Palm Reader for granted for the first time while they toured Sleepless. One gig came and went without me. Then a second, and a third.

Covid played its part along with depression and just being an adult with work to do and responsibilities to handle, but ultimately there were shows I could have attended and didn't. By the time Palm Reader announced their split in the early part of 2024, I still hadn't seen those wonderful songs live.

Five days before my second visit to 2000 Trees, I watched Palm Reader play their last ever headline show. They packed out the Rescue Rooms venue in Nottingham. It was the first time I'd seen them in their final form, a dextrous and indulgent seven-piece complete with a third guitarist and a keyboard player, each an indicator of the evolution of the UK underground’s finest band.

The final show in Nottingham was an emotional affair but, above all, a celebration. There were a few tears but very many smiles. Palm Reader tore through a set that drew from the whole of their career. They showed their every face. It was magical.

“It’s a stunning end preceded by love and tears and choruses belted out from the front row so robustly that I’ll feel them in my throat for days.”

Here at Upcote Farm, the imminence of the end casts a shadow but the honour of saluting Palm Reader into the sunset is a thrill. In between the hot dogs and beers and Brummie poutines, a string of UK bands unknowingly try to take our minds off the evening ahead.

Mouth Culture are playing by the time I arrive. Cruelty and Burner, both bands I know and like, do what Cruelty and Burner do. Guilt Trip are less familiar and provide a handy distraction for a while. Unpeople are sensational, turning in the kind of performance that might be described as levelling the place, were it not so damned fun.

Alas, the time comes. Palm Reader's final show is transcendent.

They attract a main-stage crowd for a second-stage billing. The festival’s Cave stage is not just full, but spilling out into the open air. The back and sides of the crowd are ten rows deep before it’s even under the marquee. I’m at the front, leaning on the barrier in front of the stage, eager to soak it all up one last time.

Dan Olds is back behind the drum kit. Sam Rondeau-Smith returns to play the final few songs, the last of which is ‘A Bird And Its Feathers’ and features no fewer than four guitarists, namely Rondeau-Smith and Andy Gillan flanking more recent touring additions Matt Reynolds and Joe Gosney.

Dave Musson

It’s a stunning end preceded by love and tears and choruses belted out from the front row so robustly that I’ll feel them in my throat for days.

There’s levity, too. At the side of the stage is Reynolds’ bandmate Tom Marsh, the drummer of noisy nuisances HECK and Haggard Cat, who bursts off the apron without warning and scampers up the barrier and over my shoulder before burrowing into the mosh pit.

Two shocked members of the security team directly in front of me think they’ve missed a crowd surfer and allowed him to stage dive. Marsh has no idea of the puzzlement and visible irritation he’s caused. Imagine how funny it was the second time.

Palm Reader might never have played a better show. They are at the peak of their powers. They go out on the highest of highs. McKeown addresses the audience during a long pause in the last song. He speaks of connection, neatly capturing the reason he’s here and the reason we’re all here too.

“Thank you for being here,” he says. “Thank you for always being here.”

Dave Musson

That’s what this band is all about. Palm Reader is a love I share not only with my gig-going friends but with thousands of other people who took this music from the underground and made it the central pillar of their tastes.

Music, in the end, is what matters the most. Palm Reader are generous, ethical, funny, entertaining people. They’re also a brilliant band with the discography to prove it. They mean so much to their fans.

As the very last notes of Palm Reader ring out in a tent full of shell-shocked fans, it’s clear that this is a truly special connection that will die hard.

Here’s to Devil’s Night: Thirty Years with The Crow

Cinema has changed a lot in the last thirty years. Sequels and reboots and vast comic book universes have become dominant. We experience movies differently too. A whole generation now knows only streaming. Memories of the recent past seldom seem more quaint than in the searing glow of the lights of the video store.

Cinema has changed a lot in the last thirty years. Sequels and reboots and vast comic book universes have become dominant. We experience movies differently too. A whole generation now knows only streaming. Memories of the recent past seldom seem more quaint than in the searing glow of the lights of the video store.

Before Netflix there was Blockbuster and before Blockbuster, at least in England, there was a wondrous array of independents, small chains and video rental services run out of the back of newsagents.

Borrowing a film on tape couldn't be simpler. We'd walk to the video store – by the time I was in the habit Blockbuster was more or less the only game in town – and look for a film to enjoy. Clacking through the racks, we'd pull out one box and read the bumph. Then another. And another. Streaming feels different, less tactile, but some of us were swiping through films before it was cool.

Alighting upon a choice with next to no information to back it up, we'd take it to the counter, where it would be swapped out of its meticulously designed artwork, stripped of its outward identity as if to highlight the inherent guesswork involved in taking it home and watching it. If we were lucky, the previous renter might have rewound it to the start before returning it.

“Believe me. Nothing is trivial.”

Eric Draven, The Crow (1994). Improvised by Brandon Lee.

It was in a nondescript white Blockbuster box that I discovered The Crow a few years after its theatrical run. I knew nothing of the lore or context but the contents of that VHS tape did something wonderful to my brain.

As a teenager, I struggled at life. There was no real hardship, no cause to complain about a lack of opportunity despite not coming from wealth. I just wasn't very good at it. It didn't suit me; I never felt at home or at rest. I was angry at a world I didn't recognise in myself.

I watched The Crow in the dark in the early hours of the morning, alone in an apartment I didn't want to be in, during my most difficult years. Rain tapped the windows, as of someone not-so-gently rapping. I immediately became obsessed.

The Crow is set in a neogothic facsimile of Detroit where it can't rain all the time but it seems to anyway. It drips with danger, possessed of the kind of enveloping, pervasive evil that can only originate in fiction.

The movie opens on a vast shot of the city from above, the sky teeming with fiery light, on Devil’s Night. In the world of The Crow, October 30th is an annual orgy of arson directed by the city’s criminal underworld. Smoke billows up through street grates, illuminated by lightning. Eric Draven rises from the dead and claws himself out of the grave.

This Detroit couldn't be further from a nineties suburban childhood on the south coast of England but I was seduced by it completely. The character of the place, while necessarily exaggerated to rid it of perfections, called out to the disaffected. We can never go there but we know its godforsaken streets and alleys because they are ours too.

The movie was released in the United States on 13th May 1994. It was a Friday, naturally. It was the first US feature by Alex Proyas, a 33-year-old Australian director, who took on the challenge of bringing the idiosyncratic source material to the big screen.

The production deadline was missed in the most tragic circumstances. Brandon Lee, the star of the picture, was killed in an accident on the set. Paramount exercised its right to not pick it up but Miramax stepped up to the plate in early 1994, ensuring that the darkest darkness was dragged out into the light.

Thirty years later, The Crow still has its wings. For all the mystique of its genesis, all the sideshow stories and the indescribable sadness that inevitably drifts along on the airborne vapours of the fictionalised Detroit, at the heart of the matter is a piece of art that’s both of its moment and lost in time. The novelty might have worn off but the essence remains and the movie, three decades after its release, stands tall.

The Crow isn't immune to the sins of Hollywood. It had three sequels, if they can be called that with no shared narrative thread beyond the conceit of the returning dead, and they slipped from awful to abysmal. There was a television series that was more related to the original and at least had some heart. The unwelcome reboot has finally come to pass.

City of Angels, Salvation and Wicked Prayer have the same overall premise as the original but not the black magic. On paper it was replicable; the bare bones of the plot are simple. The Crow adheres to a structure that fits neatly into narrative theory, the secret story sauce of ten thousand and one flicks before it and since. But the 1994 version has something more. It seeps into your psyche. It becomes you.

The graphic novel on which the movie is based is a deeply personal labour of love and loss by James O’Barr, a Detroiter and former US Marine who knew all about both. O’Barr grew up in foster care and cut his artistic teeth producing instructive works in the military after his fiancée had been killed by a drunk driver. O’Barr wore his bereavement like a millstone. His few public recollections are affecting even to those for whom equivalent tragedy remains mercifully out of reach.

The story of The Crow is woven through with sadness of its own. The movie was shot mostly at night at Carolco Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina. From the very first day of filming in February 1993 it was beset by a sequence of mishaps and accidents. A member of the crew was badly burned in one of them. A truck caught fire in another.

Production of The Crow was regarded and indeed reported as plagued long before Lee was killed. Production coordinator Jennifer Roth told the media that she didn’t find the unfortunate happenings at Carolco unusual. “We have a lot of stunts and effects,” she said. “I’ve been on productions before where people have died.”

By the end of the same month there was another. Lee was shot in the early hours of March 31st and passed away twelve hours later. He was 28 years old. In late April, North Carolina District Attorney Jerry Spivey announced that the cause of Lee’s death was negligence.

The investigation concluded that the broken-off tip of a dummy cartridge used to film a close-up became stuck when the dummy was removed. When the gun – now loaded with blanks – was fired at Lee by co-star Michael Massee, the tip went with it. Massee died in 2016, taken by cancer shortly after his 64th birthday. He continued to work until his passing but was haunted for life by the accident on the set of The Crow.

“I am reminded of Brandon in all things true, beautiful and strong.”

Eliza Hutton

Distraught, the cast and crew broke from production. Proyas returned to Australia and a quick decision to continue was followed by nearly two months away from the set, a rest in the shadow of heartache. The Crow had eight filming days remaining. Though not all required Lee’s presence – while those most affected were his loved ones – the push to complete the picture did pose a practical problem.

Proyas and producers Jeff Most and Edward R. Pressman completed The Crow with the use of state-of-the-art digital techniques and Lee’s stunt double. Chad Stahelski was a friend and martial arts training contemporary of Lee’s and went on to work extensively with Keanu Reeves. He was Reeves’ double in The Matrix and acted as a stunt coordinator on the two remaining films of the original trilogy. Twenty years after standing in for Lee, Stahelski directed the smash hit that ignited the John Wick franchise.

The circumstances around the film are often said to give it that extra spark, a particular kind of gothic mystique, but the truth is more mechanical. After Lee’s death, Proyas and the writers made significant changes to the script that were geared towards softening the story.

Michael Berryman’s character, a guide for souls in purgatory by the name of the Skull Cowboy, was to serve as a narrative spirit for Draven. He had to be cut reportedly because Berryman and Lee had important remaining scenes still on the schedule.

Without the Skull Cowboy’s guilelessly spelled-out plot signposts, The Crow feels tighter. A straightforward anti-hero comic book movie overloaded with characters larger than life, “turned out to be a really nice, beautiful love story,” according to Ernie Hudson, who played Detroit cop Darryl Albrecht. If that was the production’s tribute to its fallen star, it was a fitting one.

After his tortured resurrection, Draven picks off the street gang who murdered him and his fiancée, Shelly Webster (Sofia Shinas), 365 nights earlier.

He stabs Tin Tin (Laurence Mason) to death with his own throwing knives in an alleyway. He injects junkie Funboy (Massee) with syringes of morphine. He incinerates ringleader T-Bird (David Patrick Kelly) in a runaway car with a lapful of dynamite. Seventeen nameless bodies later, he throws Skank (Angel David) out of a window onto a police cruiser.

All the while, Michael Wincott’s übergothic Detroit criminal overlord Top Dollar is guided towards a realisation of what’s happening on his watch. In an epic final showdown, the crow notches a kill of its own before a freshly mortal Draven and Top Dollar slug it out with swords on the church roof overlooking the graveyard. Top Dollar meets a grisly end and Draven returns to the earth.

It really is that linear. The Crow emerged from its tragic retooling as a masterful demonstration of the value of soul over complexity. Simplicity allows the story to shine and it’s the performance of the star that elevates it to something truly special.

Lee is transcendent. Regarded by the industry as a martial artist and supporting actor but with his own designs on being a leading man, his embodiment of Eric Draven feels like a fulfilment of destiny. Actor and character are one.

The flame that flickers around the edges of The Crow is the result not only of Lee’s death, but of his so fully inhabiting a deathless avenger zombie – mortality and eternity, truth and fiction, all rolled into one painted face and preserved forever in the most awful way.

“Do you see my smile in my words, sad and evil?”

Eric Draven, The Crow (1989) by James O’Barr

Proyas and Lee lobbied for the entire picture to be shot in black and white. The studio wouldn’t sign that off and Proyas elected to wash out the colour instead. David Lynch is a lover of what he calls happy accidents. Proyas stuck the landing and the consequent style of The Crow is one happy accident that seems to draw to it the dark hearts and sorry souls.

In the early- to mid-nineties, fashion and music were in flux. There’s something very 1994 about how The Crow looks and sounds, but so much of its styling and soundtrack proved timeless, in subcultural standards if not the mainstream, and that’s a big part of its durability.

The original soundtrack is thought of as one of the best there’s ever been. As a lover of The Cure and the proud owner of a Nine Inch Nails tattoo that required three painful days in the chair, it’s fair to say there are some songs in The Crow that mean a lot to me. But Graeme Revell’s haunting score is too often overlooked and is essential to the cult success of the film.

When I first saw The Crow I was a sensitive and angry kid, confused and irritated by the chore of existence. The film appealed to me. I was enthralled by the pictures it painted, by the notion of vengeance, by the love story at its core, by the music, by each kill and every cheesy one-liner delivered in the midst of a performance for the ages.

I’ve seen The Crow more times than is necessary or healthy. I know it inside out and back to front, body by body and word for word. By that measure alone, one might label it my favourite film. But it’s not that. It’s more. The smoke of a Detroit that never was has left its scent on my skin and in the threads of my clothes. We all absorb a little of our cultures, and I’ve been passively inhaling The Crow for more nearly thirty years.

In a very real sense, The Crow has been one of few constants in my life. It took me through school and university, out of adolescence and into adulthood. It shaped my taste in music and art as well as cinema. It made me appreciate atmosphere and mood. Though I live out here in the mundanity of the real world, The Crow has become my portal to the fictional one. It’s the lens through which I view the land of make-believe.

As the film adaptation of O’Barr’s gut-wrenching tale reaches its thirtieth anniversary, I’m still that sensitive and angry kid. It’s just that I have other layers now, too: experience, maturity, professionalism, insight and knowledge, artistic outlets for what would otherwise be a ruinous temper. I’ve learned how to process my existence in the world.

I love, and I’m loved. I recognise the emotional intensity of The Crow as an adult in ways I never could have as a teenager. Buildings burn. People die. But real love is forever.

A Brandane Heart

Despite a life of relative contentment I am not a restful man. In my mind doubt and pessimism reign, a perpetual fury of this and that, seldom at ease. The Isle of Bute – whether I’m there in body or spirit – has always been my sanctuary.

Despite a life of relative contentment I am not a restful man. In my mind doubt and pessimism reign, a perpetual fury of this and that, seldom at ease. The Isle of Bute – whether I’m there in body or spirit – has always been my sanctuary.

Bute is moored peacefully in the Firth of Clyde, perfectly west as the crow flies of Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city by population. The bustle of Buchanan Street is a world away from the sleepy splendour of Scalpsie Bay beach or Ettrick Bay and its postcard view of Arran.

The Caledonian MacBrayne car ferries Argyle and Bute aren’t the vessels beloved of my childhood but they look a lot like them. They sail between the mainland terminal in the village of Wemyss Bay and Rothesay, my ancestral island home and as close as Bute gets to crowded.

Rothesay is in many ways a typical British seaside resort, its most colourful days experienced by now-distant generations and its celebrated buildings beginning to crumble around the newsreel reminiscences of holidays gone by. Though not without its charm, Rothesay isn’t blessed with the phenomenal beauty so prominent in the parts of the island where nature remains dominant.

Just around the coast from Rothesay is Ascog, home to a handful of islanders but to me a beach of shingle and slate-grey sand, punctuated by seabound pipes and the cherry red of an old-fashioned telephone box that looms in the corner of one’s vision when sitting on the promenade bench. This is my mother’s favourite spot on the island and the only place in the world where we share childhood memories.

From that bench we watched Argyle and Bute pass one another on the waves the day before we said goodbye to my grandmother. My first visit in many years to this place I love so much was a sudden and unwanted holiday that uncovered long forgotten summer joys in the shadow of loss and heartbreak.

Rothesay and Bute have a richer history than is suggested by their modest existence today. The island has a past studded with headlines that betray its status as just a little bit more special than the average British island.

Its number one tourist attraction according to TripAdvisor and modern lore is not the seals who sun themselves on the rocks, or the herons who squawk their way over the grand houses of Craigmore to settle on the pebbles after dark, but the Victorian public convenience perched on the seafront in Rothesay, beautifully preserved with most of its original fitments and open to visitors with a penny to spend.

The building was commissioned in 1899 by the Rothesay Harbour Trust, a decorative and lavish statement of lavatorial grandeur quite in keeping with the town’s Victorian golden age. Rothesay was a much loved holiday destination for the ladies and gentlemen of the day. When the Waverley – the world’s last seagoing paddle steamer – sails by, it’s easy to imagine their ghosts on deck, waving to the rather less numerous tourists of today as they tackle the putting greens overlooking the water.

Peer further inland and they would discover a side to Rothesay they would never have imagined.

In late 2015 Bute welcomed 24 families of Syrian refugees and there were more to follow. The inevitable xenophobic backlash was quashed by the forthright advocacy of the local newspaper editor. The shop fronts and restaurants that popped up in the years that followed are testament to their successful integration. Helmi’s Bakery, a popular Syrian patisserie opened by Tasnim and Mohamed across East Princes Street from the harbour, now has a presence on the mainland.

Indeed, Bute has a proud heritage when it comes to offering a safe refuge. In between the Victorian visitors in the 19th Century and the burgeoning Syrian community in the 21st there came an influx of new islanders from the mainland. They were the Butemen of the future. Children of the War.

The waters around the island made Bute an ideal naval site during World War II and both on- and off-shore it provided a base for various military operations. No sooner had war been declared than Rothesay Pavilion was transformed into the island’s reception centre for evacuees.

It’s here that my relationship with this rugged, wonderful, curious place begins. My great-grandparents, Jimmy and Jeanne, made their life in Rothesay and added significantly to its population. One of their children, my grandmother, Prue, was born just as the War began. She left Scotland for Birmingham at the age of 18 and returned after Joe, my grandfather, passed away in 1991.

We buried her with her parents in the grounds of Saint Mary’s Chapel in September 2020 after a service with restricted attendance, mandatory face masks and no pallbearers. I’ve never known a sadness like it.

Not many people of my age meet their great-grandparents but I was lucky enough to know one of mine. Jimmy lived to the age of 100 and, as a lover of pipe bands, he couldn’t have been in a better place. In his younger days he worked as a slater, a role that afforded him an apprentice, Hector, upon whom was bestowed the responsibility of legging it to the betting shop to indulge another of his great passions.

He loved nothing in life more than his family, all three younger generations of us. He was the patriarchal presence of those childhood holidays, the family’s triangulation point. Through him, relatives who would be distant in other families became close in ours. He was proud that his longevity in life facilitated that.

I have many happy memories of Jimmy but my grandfather died in his early fifties. I was old enough to know and remember him but young enough that most of those memories fade together until they’re not really memories at all. They were made not in Birmingham but on Bute.

One such memory emerged in the form of a photograph inherited from the albums left in my late gran’s flat overlooking the island’s visitor centre and the harbour beyond.

Somewhere in the Bute countryside on one of our many fishing trips, my skinny and nobbly-kneed former self takes a brief sidestep out of his youthful shyness and shouts at the top of his little lungs. Standing to my left, sporting a beaming smile and a distinctive pair of sunglasses, is my granddad.

This snapshot could have been taken on any one of those outings. I have no idea. I don’t recognise the landscape or my clothing. But I can smell his tobacco after more than thirty years, and I remember now that he used to stir his tea with his finger as if it were a normal thing to do.

Rothesay’s popularity over the years means that there are hundreds of thousands of people in Scotland, England and all over the world with hazy memories of the Isle of Bute. It’s different when it’s family. Whether we were fishing at Ascog or Kilchattan Bay or Loch Fad, or skimming stones into Kames Bay on the east of the island and anywhere else we could find them, we did so with a sense of home. We didn’t all live there but none among us were tourists.

On my most recent visit, my mum said something later corroborated by two of my colleagues whose coincidental Bute roots are equal to hers and more tangible by far than mine. The island doesn’t sound much, now the last echoes of more prosperous summers are long forgotten, but when you’re there as family it gets under your skin, somehow. It’s easy to fall in love with it and impossible to let it go.

That photograph, taken elsewhere, would still represent happy, sunny days with my grandparents no matter what. Taken where it was, it’s as much about the place as the people.

Within that single frame is a world lived by generations since lost. Not a holiday, but everyday. Food shopping and picking up the paper from the newsagent. Popping in to see great aunts and second cousins for a cuppa. The mundanity of routine, tucked away in the water. And me, a little boy from the south coast of England, loving every moment of it because I felt like I belonged.

Bute is part of my identity. I adore the island for the memories it’s given me, for the home it’s been for my family and for a beautiful landscape I’d choose over anywhere else in the British Isles.

I’ll never feel about anywhere else the way I feel driving off the green ramp of the ferry, Rothesay stretching out in front of me as a lifetime of memories reignite. I’ll never taste vanilla ice cream better than Zavaroni’s. I’ll never capture or articulate the essence of my childhood that lurks just out of reach on every visit. But I like to know it’s there.